Mikael Vesavuori

Domestication (The Cannibal)

The World in Becoming

…There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns — the ones we don't know we don't know.

- Donald Rumsfeld, February 12, 2002

Imagine a world in which every corner is mapped, every decision is preordained, all possible actions are always and only sanctioned by some external power, nothing that can be spontaneously unearthed remains to explore, sense or interact with.

All information and all layers of knowledge are already exposed to everyone—

—It is a world which is predicated on possessing information. Those who possess no information are the new poor.

Everyone is poor when it comes to information, but some are entitled to sift through information and delegate a society that has become a permanent bureaucracy.

Sources of knowledge other than scientific proof and raw quantifiable, processable data are deemed, at best, as intellectual embellishment, a sign of highly cultured senses—a sparkly merit in the curriculum vitae. Such information would unlikely be valued as critical, if push comes to shove, which it has always-already come down to.

The condition is therefore permanent crisis. Always at a loss, always lacking, every action is an expenditure of resources.

The sensory world is made the frontier of entertainment-aesthetics, simulated with ultra high-end technology and stimulated by neuropsychological means, mastered by a new era of black sorcerers who are now called medical professionals, scientists and psychologists.

It may be hard or even impossible to truly identify what that world would be like—is such total stasis of personal and affective exploration possible? For indeed it is a total stasis, a winding-down of mechanisms that previously had continuously liquified borders, and made people transgress what is expected of them, forming actions that question what is possible.

But: nothing remains to add to this total world-image-in-becoming, only elements to be removed, if even that. A dichotomy is assembled consisting of addition or subtraction: allowing or disallowing, entering or exiting, gaining by expending, expending to gain. The initial arithmetic is simple grade-school math. It is when time and prediction of future histories enters the equation that the bureaucratic mindset begins to kick in.

The spectacular qualities of this vision may seem far-fetched and as Markus Gabriel has written about, all-encompassing world-views are logically impossible. An object or concept—a certain society, a certain Utopia, a certain community—cannot contain every possibility or permutation or use, whether intended or not, or humanly knowable or not. It cannot, for that matter, contain every other object as a by-product inclusion. That is: a world-view cannot be singularly shared or understood, and it cannot contain every type of possibility or answer to every kind of contingency. Objects or concepts are not infinitely malleable. The promise of one certain mega-object, the all-encompassing democratic world-view, has to some extent been created specifically to force everything within its own framework, even that which threatens to destroy it.

Democracy and knowledge have been brought to the fore as ideal, true answers about how to share values about human life as the ultimate prize, and taking as its mission to dispel false gods and superstitions with absolute scientific precision. All resistance will be accepted as ideas, but never legally tolerated when taken into action. Democracy in its 21st Century version is a glass cage: smooth, transparent, bordered, hermetic, a position to be viewed within and view others from.

Threat is from the future. It is what might come next. Its eventual location and ultimate extent are undefined. Its nature is open-ended. It is not just that it is not: it is not in a way that is never over. We can never be done with it. Even if a clear and present danger materializes in the present, it is still not over.

The future of threat is forever.

- Brian Massumi, ”The Future Birth of the Affective Fact”

Collectively, we live in a very specific age of fear. Fears within this logic could be attributed to adding or subtracting something.

We fear that which is strange and added onto our own lives and we feel alien about ourselves. It is seen in xenophobia, hatred of those who do not conform to preset qualities, workplace harassment, or non-normative behaviors. Walls are built and people are interrogated for growing beards, and children fleeing wars are forcefully kept away with multi-level barbed wire barricades. This type of fear has its strongest evidence in all various kinds of hate of the Other.

UK submarine launching a trial Trident II nuclear warhead. The Vanguard class submarines are always operational and ready to launch a nuclear attack at any place on earth. They move globally and their location is a well-kept secret.

We also intimately fear that which risks being taken from us, by way of physical and health issues, by terrorism, or even by forceful, distant legislative action. Here, superstition, paranoia, and latent invisible qualities become fearful. We may also witness this through another lack: apathy, for example seen in how a high degree of young people or children seem to lose their interest in creating (except with technological, and simplified tools), or how increasing medicalization restricts thought patterns and actions that are deemed extreme, unwanted or diseased. Many feel discontent with their day-to-day lives; the numbers of prescriptions for anti-depressants keep rising; political activists are suddenly actively resisting forms of participation and debate several hundred years old; disbelief is rising within both religious, secular and social movements. Impossibility of thinking and acting meaningfully renders one in a state of hopelessness—often the beginning of powerful downward spirals. In the broader scope, those spirals turn into exclusion and patterns form when more and more people share those spiraling paths. In politics we are already contemplating how to deal with those who are unable to keep up—in any aspect whatsoever—and we count them in the millions, worldwide. Even entire generations may be doomed in some places.

During the last few hundred years, much of humanity has gone through what may be the birth of an ”absolute truth” system, exemplified in part by the far end of radical Silicon Valley scientism. The cult of knowledge in general, enforced in academia by the unwitting mouthpiece known as the humanities—who seem to have been co-opted by an intensely lobbying tech sector and conservative politicians who value numbers more than facts—has taken hold and practically become the heir to both religion and the greater field of science.

Literal thought aims at being a reflection of reality as it is—it claims just to tell you the way things are. We tend to say that's the best kind of thought. Technical thought, for instance, aims to be literal. Such thought intends to be unambiguous; it may not succeed, but it aims that way—to know something as exactly what it is. Owen Barfield has compared such literal thought to idol worship. If you make an idol, it may stand in at first for some force which is greater than itself, or for some spiritual energy. But gradually the idol is taken to be it—literally; and therefore you give supreme value to that object. We could say that in a way we are worshiping our words and thoughts, insofar as they claim to be descriptions or statements about reality just as it is.

- David Bohm, "On Dialogue"

The devices and tropes of current-era dispositional power and knowledge-generating systems however seem to have reached their respective ends, with the primitive fear instinct shapeshifting as a reaction to the lack of meaningful insight or correction through dispositional force. Yet it is defiantly believed that more knowledge—as mere quantitative matter—will create conditions for more rational understanding and by itself create a shared sense of humanity: it seems as the ”what” is mixed up with the ”how”. For all of the things knowledge can do by itself, it has been utterly failing in the main mission of humanism: to promote coexistence.

…Those creating vast bureaucratic systems will almost never admit what their values really are. […] Normally they will […] insist that they are acting in the name of efficiency, or "rationality". But in fact this language always turns out to be intentionally vague, even nonsensical. The term "rationality" is an excellent case in point here. A "rational" person is someone who is able to make basic logical connections and assess reality in a non-delusional fashion. In other words, someone who isn't crazy. Anyone who claims to base their politics on rationality—and this is true on the left as well as on the right—is claiming that anyone who disagrees with them might as well be insane, which is about as arrogant a position as one could possibly take. Or else, they're using "rationality" as a synonym for "technical efficiency", and thus focusing on how they are going about something because they do no wish to talk about what it is they are ultimately going about.

- David Graeber, ”The Utopia of Rules”

The struggle for knowledge, as a global mission, is grounded in a fundamentally humanist conviction of knowledge's emancipatory potential. When people know, understand and can make rational decisions based on qualitative and quantitive data, things are said to improve, and progress as a greater project can continue along its deterministic path to non-religious savior. With no God at the steering wheel, secular societies make a claim for the society-car being smart enough to steer itself to an indeterminate Utopia. This knowledge surpasses what our infrastructures can contain, filling secret server halls, laptop hard drives, apocalypse-proof vaults, and all the world's academic institutions, which are still not enough—our accumulated knowledge is so vast.

Designer Kenya Hara has written that one of our current mannerisms is to say ”I know” as an answer to various statements or questions we may face. This state of always ”knowing” he finds problematic and very much a contemporary predicament. With ever greater access to spaces of data, as well as living in an era largely dictated by technological and statistical processes, one would expect that we in fact do know a great deal. But what does it mean to truly know? The acts of thinking, such as recognizing, collating, dismantling, synthesizing, analyzing and reflecting information are effectively nullified in favor of simple recollection when demands are lowered. This pattern is similarly shared within education, where testing (and its focus on recollection) has been absolute doctrine for quite some time. A cognitive precariat begins to grow around highly specialized jobs, with transdisciplinary knowledge-workers becoming more attractive for employers within innovation industries. Innovation becomes the next hard currency when applied to such preordained solutions that match ”important needs”, or rather, strategic social futures built by a select few for the benefit of ”all”.

The idea itself of knowledge-attainment could be understood as a way of providing answers to our most worrisome questions. We know, at the very least, that the Other has taken a multitude of shapes over the course of human history: among others, as the non-national (the foreigner), the barbarian, the gypsy, the misfit, the physiologically deformed, numerous racialized peoples and of course the general non-conformists. Fear may well be an evergreen problem—one that is unsolvable and permanently attached to the human condition.

With knowing comes not-knowing, a cousin of fear, so often grounded in the unclear, covert and ambient processes not immediately available to us, striking us as plausibly devious and definitely frightening. The response has been, even in the military, to offer a greater sense of transparency, derestricting and allowing access to knowledge, with a goal of unlocking real ways of understanding the raw data and proceedings of the world at large. The rhetoric often goes that something hidden is always hidden for a reason—so it makes paradoxical sense to hide the fearful in plain sight, like in an elected office or boardroom or cell tower.

With transparency comes also the attached concept of opacity—to not see through. A contemporary rhetorical tactic has therefore been to provide excess information in response to a perceived lack of information. While the tactic seems less fearful, it allows a larger variety of speculations to erupt, creating great disorder in the general discourse and opening for a large number of possible (mis)readings. One is plunged into the other side of fear, that which comes from the overactive imagination, similar to the brain's way of piecing together non-existing sense data in a totally black room. Paranoia unfolds. Either end of this duality, taken to their various extremes, creates a prolonged sense of terror which is never linked to concrete physical manifestations.

Strong government and intensive surveillance exists in order to grant a certain kind of safety which millions happily enjoy everyday. Its material qualities are visible, strangely prevalent and rapidly instantiated where needed, yet it often feels light as a feather, invisible to the eye and non-intrusive to the body. Superficially, this setup is benign towards its citizens—with the aim of better counter-acting forces wishing to impede, destroy and block the goals of such governments—but there is little to suggest that fear and terror can be counter-acted by such apparati. Rationalist administrationism as a governing principle is expected to produce conditions that are strictly regulated—that is its raison d'être. It constantly plays with notions of visibility and invisibility.

Measurements, flows and statistics matter a lot to the administrator. Indecisions and fluctuating habits of people are seen as aberrant, and therefore prone to suspicion and surveillance. That which does not fit into models of order becomes encapsulated and questioned. It is, as far as human agency goes, indeed an end of time, a historical standstill, a need to bodily submit to very precisely formulated ideologies taking all the more physical forms. This is when the immaterial qualities are summoned onto your own body as you shift from ”public individual” to ”incarcerated individual”. If not in a correctional facility, then perhaps a chat in a detaining room, or under the right conditions, spending some time in an unregulated black site run by various national security services. Just to make sure.

Collective social fears are perhaps ever more present than ever, and knowledge has done little to exterminate the frightening folds and cracks of a not-so-smooth coexistence. Information overburdens us at every step into the future, but fears keep lingering on. In this age, the greatest societal fear is that of the potentially overlooked—negated, invisible, inverted—potentially waiting to make its move on us. What and from where we do not know—the belief is, as Massumi writes, all that is needed for it to be true.

Chantal Mouffe is known for her theories around agonism which works as a way of negotiating perspectives through meaning-making conflict. Agonism goes against many traditional ideas of privileging consensus and deliberative practices, commonly vouched for by mainstream politics and also thinkers like Jürgen Habermas. Instead, agonism makes difference the key issue in granting politics a decisive possibility-space—politics which should enforce acceptance of rights and individual or collective space for such differences to unfold. We must learn to coexist without subduing, through law or violence, each and every thing we do not have in common.

Whenever someone starts talking about the "free market," it's a good idea to look around for the man with the gun. He's never far away. [… ] We are now so used to the idea that we at least could call the police to resolve virtually any difficult circumstance that many of us find it difficult to even imagine what people would have done before this was possible. Because, in fact, for the vast majority of people throughout history—even those who lived in large cities—there were simply no authorities to call in such circumstances. Or, at least, no impersonal bureaucratic ones who were, like the modern police, empowered to impose arbitrary resolutions backed by the threat of force.

- David Graeber, ”The Utopia of Rules”

The sociological concept of ”paramount reality” (see for example Stanley Cohen's ”Escape Attempts”) is a way of mapping the outer borders of what constitutes the absolute premises of the normative, accepted life. Trying to flee, by engaging in activities and lifestyles that are bound to enclaves or other demarcated areas, gives only temporary relief from the oppressive paramount, everyday reality. As the borders close in on what exactly forms the normalized lifestyle and queer, rhizomatic cultures become segregated, the absolute realism of the bureaucratic state harshly resists the poetic qualities of playful subcultures. As cultures become assimilated, their strangeness and non-conformism goes from edgy to a standard inventory available within the overall culture. As borders dissipate and are internalized through such generic versions, latent conflicts are made less hostile just as much as natural differences in subcultures become disproven or unlawful if not deemed integratable—an extinction level event for difference markers. We no longer need to live side-by-side, when we are all one.

What is feared has seldom been the visible. Indeed, what mankind has done throughout history is to fear the indexical: that which marks sickness, disease, uneasy assimilation, alterity or the outright abnormal. Violence has been, and keeps on being, perpetrated by individuals and states everywhere, everyday, to those people and things that are not compliant to regulations, norms, ideology, law and whatever else marks the local yardstick of true being. The process may therefore be crude, powerful, elastic, all-encompassing, word-based or whatever else, as long as it manifests itself through reaction: subservience, acceptance of ideological protocols, even just waiting until the light is green before crossing the sidewalk.

Teratology is the study of the abnormal and the process just mentioned is one of concretely applied political teratology. This preoccupation with the abnormal is one of many evidences of the state as being markedly different and above the individual, as that same teratology is not possible to be wielded by the sole individual. The power to exercise teratological examinations of groups from a decidedly different vantage point references an enlarged frame within Louis Althusser's appellation example: by pointing at the deviant, the deviant must confront an immediate asymmetrical power relation—the non-conformist must prove his innocence or standardization, where no future historio-revisionist small-print newspaper notice will ever fully compensate for the damage done by the pointing-out.

The perception of object-related fears is always context-dependent, shaped by cultural roles, expectations, and moralities that surround or link up to the emotional registers of human experience. Amid this confluence of factors, religions serve as one of the most powerful means by which moral and emotional agency are situated and constituted in cultural contexts that are intersubjective, historically patterned, and energized by those things which promise their doom. These templates and patterns of interpretations help communities form ways of understanding our world and formulating convictions about it. In the context of teratologies, then, what is compelling about fear and its modes of interpretations are the responses it induces. The names and narrations given to these experiences, particularly as they are housed in religious traditions, invariably promise not just to name the fearful unknowns but—by positioning this terror against pieties—to offer control and displacement as well.

- Jason C. Bivins, ”By Demons Driven: Religious Teratologies”

Knowledge, to understand the functions of the world in minute detail, has been thought to reduce anxieties, granting swiftness to undertakings, meaning one can make better choices in less time—ultimately creating the prerequisite conditions for stability. With universal understanding and proper information, growth becomes—at its best—exponential as former skills are internalized, codified and reproduced. Societies built on firm principles of knowledge sharing and knowledge production have the power to reify their intellectual prowess in ways impossible during chaotic times and strife. Conflict may create sparks of intellectual and intuitive energies, but a lot is at risk of becoming lost and undermined. Thus, global politics of stability enter the fold as complex national and international relations are tested every day.

In stable societies, lives are expected to be improved gradually and methodically—transcending from the barbarous to the sublime—when not needing to fear civil unrest or external enemies. As a matter of political course, this makes a lot of sense as rulers can remain unharmed from the masses and be distanced from the processes of the never-regulated-enough daily lives of the communities. Critiques of wage-labor alienation and specialization of the work force may therefore just as well be applied to administrators of state. With such distancing comes also a multitude of apparati needed to remain in power. Where religious institutions had previously controlled land, knowledge and property with the backing of some God or another—then metamorphosing into the despot or king with his dually sacred and corporal backup—the atheist State became a totally different animal in regard to power relations, and certainly so when allied with global (private) finance. Stability has become the modern gateway drug to power. Biopower and continual reconditioning of the human capital (work force) is the safeguard before a collapse that seems to be on permanent stand-by.

Stability in turn poses obvious questions about political inflexibility, as regimes that have fallen and risen during the last 100 years have not always been quick to change when public opinion shifts. The lure of raw, total, physical power remains strong, especially where democratic or hyper-modern conceptions of soft or hidden power are not yet fully developed.

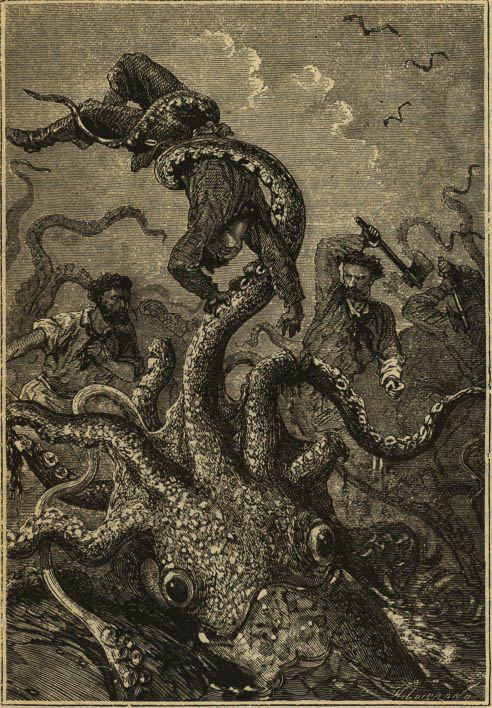

Recall the constantly shifting enemy state in Orwell's 1984: it does not matter who the enemy is, under which condition conflict is waged, how quickly positions change, just as long as there is an identifiable culprit even if being historically inconsistent. For the atheist State, its inventory of apparati must be well-oiled and enemies kept simultaneously as visualized and real as possible, just as much as indeterminate fears must always be readied. As in the Platonic world of computer programming or in object-oriented ontology, concepts and affordances are seen as manifested and instantiated through ”objects”—the object is used as a term for both animate and inanimate matter. This is partly because we cannot perceive all of the aspects of any given object, which is the precise quality that makes fear so powerful an object. I believe that the concept of contemporary Fear has become manifest in the complex object I wish to call the Cannibal.

The Cannibal exists in this type of realism where knowledge and its manifestations—such as vision technologies, big data, advanced telecommunications, global bureaucratic post-democratic states—more than ever constitute the frame of our world in becoming. After assessing intelligence and locating the enemy, they remain only to be domesticated or destroyed. Their time has been measured into the dictated operational timeframe of the allocated response team. In the case of imminent destruction, surgically delivered payloads are exacted upon the target; taxes are paid for covert operatives traveling on second class international regular flight lines; bribes are given to the right officials; market-based overhead prices are calculated for the minimal necessary quantity of strategic warheads, laser-guided deep-penetrating missiles or expanding hollow point bullets needed to dispose of the enemy in the most expedient manner. It is not an aesthetics of violence as excess—on the contrary, it is a minimalist aesthetics of absolute reductivity and informed mathematics. A cost-benefit model is produced with the same methods that guide both financially successful car factories and publicly owned hospitals. Your life may well have a precisely calculated cost attached to it.